Applications are still open for Arts Camp and Arts Academy. Programs fill quickly—submit your app today!

Faith, trust, and fairy dust

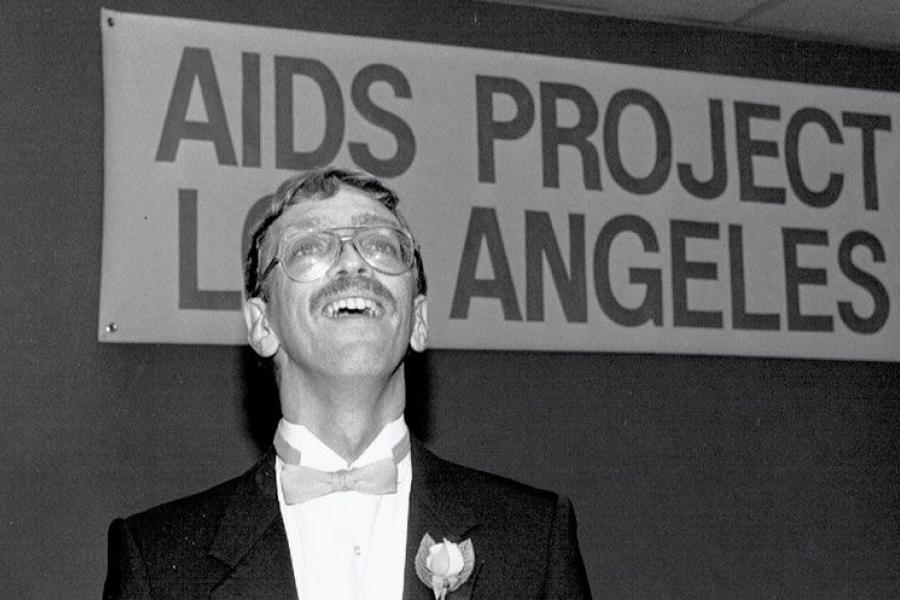

Interlochen Arts Camp alumnus Steve Pieters shares his journey of surviving—and thriving—with AIDS.

Editor's Note: Rev. Steve Pieters passed away on July 8, 2023 in Los Angeles, California at the age of 70. This article, based on a 2019 interview with Pieters, first appeared in the November/December 2019 edition of Crescendo magazine.

Each December, we remember the millions of lives that have been lost or affected by acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) during AIDS Awareness Month.

We may never know how many Interlochen alumni have been affected by HIV or AIDS. We do know that dozens of alumni have lent their time and talents to the cause as advocates and researchers, all hoping to end the progression of a global pandemic.

Today, AIDS is manageable with proper medication. But in the 1980s, medical science had few answers for those diagnosed with AIDS. It was within this reality that Steve Pieters (IAC/NMC 68-69) began his battle with AIDS—a battle that he is still winning 34 years later, thanks to his faith, medical advisors, and love of musical theatre.

Pieters first encountered theatre as a boy in Andover, Mass. “I loved musicals from the time that I first saw Peter Pan with Mary Martin on TV,” he said in a recent interview with Crescendo. “My father would sit me down in front of his record player with the original cast albums of South Pacific and My Fair Lady. I just loved them. Then, I saw the production of Oklahoma! at Phillips Academy, and there was just something about it. I knew that that’s what I wanted to do.”

In high school, Pieters discovered Interlochen Arts Camp. “It was an extraordinary experience,” he said. “It was the first time that I really met a bunch of other kids who were into the arts—and other boys who I sensed were a lot like me.”

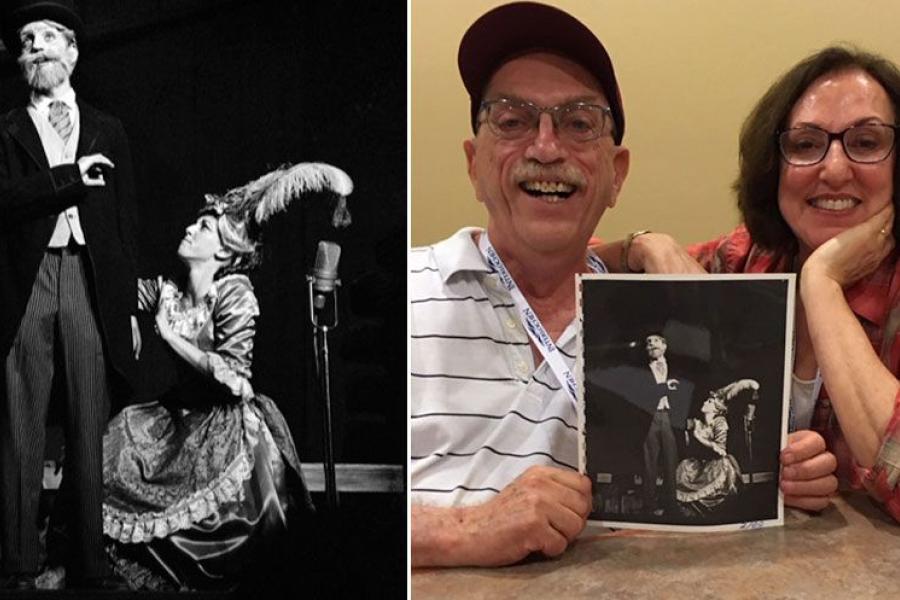

Pieters excelled at Interlochen, earning leading roles in Lil’ Abner, The Sorcerer, and How to Succeed in Business Without Really Trying and singing the baritone solos in Weber’s Mass. He was also commended by the Drama Division as an alternate for the Outstanding Drama scholarship.

After high school, Pieters continued his study of theatre at Northwestern University in Evanston, Ill. While living in Chicago, Pieters was invited to attend the Metropolitan Community Church (MCC).

“At that time, there weren’t a lot of churches that welcomed gay and lesbian people,” he said. “The MCC was founded as a safe place for those of us who were LGBT to worship God together. I started going to church there, and I had a spiritual awakening. I felt a call to the ministry. It was one of the clearest moments I have ever had.”

Pieters enrolled in McCormick Theological Seminary, and completed his divinity studies three years later. Shortly after, he was offered a pastoral position at an MCC church in Hartford, Conn. “It was not easy being gay in Hartford at the time,” Pieters said. “There were three suicides in my 45-member congregation in my first year. There were protests outside our church by various groups who thought we shouldn’t exist. Most of the people who came to my church had a hard time in life because they were LGBT, and I tried to help them see that they were good people.”

By 1982, Pieters was physically and spiritually burned out. He left Hartford and moved to Los Angeles. There, his physical malaise became severe illness.

“I had hepatitis, mono, herpes, shingles…. I caught everything as my immune system shut down,” Pieters said. “In 1984, I was diagnosed with stage 4 lymphoma and Kaposi sarcoma, which also gave me my diagnosis of full-blown AIDS. My doctors gave me eight months to live.”

Devastated by his diagnosis, Pieters, then the associate pastor of an MCC church in Hollywood, was invited to preach the upcoming Easter sermon. “It was one of the most valuable gifts anyone has ever given me,” Pieters said. “As I reflected on what it meant to believe in the resurrection of Christ as a person who was about to die of a very stigmatized disease, I thought, ‘If God is greater than the death of Jesus, God is greater than AIDS.’”

Pieters was also inspired by Dr. Alexandra Levine, who remains his physician to this day. “She told me, ‘You in the church have more to offer than I do in medicine,’” Pieters said. “But she also told me that there are no one-hundred-percents in medicine. If 0.001% of patients survive, why not believe it could be me?”

Bolstered by his faith and his physician, Pieters developed his own unique treatment plan through research and intuition. “I studied vitamins and nutrition, tried to feed my body as well as I could, and exercised every day,” Pieters said. “But most importantly, I enjoyed life.”

In a season of life that would have brought many grief, Pieters leaned in to joy. “I pursued laughter like it was a medicine,” he said. “I would make myself do it two to three times per day—big, hearty belly laughs—just like you would take a medication. I would watch I Love Lucy, M*A*S*H, Golden Girls, Cheers… anything that made me laugh. Finding joy in the face of all the horror that I was experiencing was a gift of grace.”

Pieters also found joy in his lifelong love of musical theatre, which he also treated as part of his therapy. “I would drive around the freeways of Los Angeles singing along with original cast albums and Judy Garland at Carnegie Hall,” he said. “It filled my heart with joy that I could still sing. I also went to the theatre to see inspiring plays, musicals, and operas. All that gave me a sense of life.”

Pieters’ treatment program worked: He outlived his eight-month diagnosis. In 1985, Dr. Levine invited Pieters to take part in a drug trial that she was leading, the now-infamous suramin trial. Pieters became Patient One.

“Within six months, both of my cancers were in complete remission,” Pieters said. The other 89 participants were not as fortunate: The drug’s toxicity killed 20% of the patients, and most of the remainder died of AIDS-related illnesses within two years. Pieters is one of only two surviving participants.

Although Pieters survived, it was a very near miss. “Suramin blew out my adrenal glands, and I was so close to death that they brought me into the hospital,” Pieters said. “I went blind, lost my hair, was paralyzed on one side of my body, and suffered severe neuromuscular damage. Although it put me into remission, the drug was a complete disaster.”

By March of 1986, Pieters was starting to heal from the effects of suramin, and since the trial, both cancers have been in remission. With his health recovering, Pieters accepted a position as field director of the MCC’s AIDS ministry. Through the position, Pieters traveled around the world to share messages of awareness, healing, and hope with religious and secular audiences on stage, screen, and air.

In 1993, Pieters was one of 12 religious leaders invited to attend a prayer breakfast at the White House under the Clinton administration. “Perhaps because I was the only person with AIDS, they sat me right next to President Clinton,” Pieters recalled. “It was an extraordinary honor to speak truth to power, quite literally, and share with the president the importance of speaking out on HIV issues.”

In another memorable moment, Pieters was asked to introduce Coretta Scott King at a conference on AIDS in the African-American community. “It was an extraordinary honor to write and deliver an introduction to a woman who knew what it was like to live with the constant threat of death, much like those of us who are living and working with AIDS,” he said. “After I introduced her, she gave me a great big hug and held me tight for what seemed like a minute. It was so significant for the audience to see the African-American community embracing the white gay community just as AIDS was hitting the African-American community.”

Pieters has also put his Interlochen training to work on the speaking circuit. His signature tap dance—a sign of his defiance of the disease, first given from the pulpit on that fateful Easter Sunday—has made appearances at numerous other engagements, including one of actress Elizabeth Taylor’s high-profile AIDS fundraisers. “I got up, told them my story, and then, in front of Gene Kelly, Elizabeth Taylor, and about 250 major celebrities, I shuffled off to Buffalo,” Pieters quipped.

Indeed, 34 years after his diagnosis, Pieters is still dancing. He continues to travel and speak, although the frequency has slowed somewhat. He’s also still singing. For more than 25 years, he’s been a proud member of the Gay Men’s Chorus of Los Angeles. “l love it: It’s an incredible community and a great arts organization,” he said. “I still get such a kick out of performing: watching the curtain come up, producing music with 250 other men, and enjoying the feeling of making harmony. Conveying the beauty of life through music is an extraordinary gift.”

In early October, Pieters donated several of his works, including his 1991 book “I’m Still Dancing,” several articles, and a recording of his interview with Tammy Faye Bakker on the PTL Club to the Smithsonian Institution. The highlight of the collection is a fairy wand that Pieters has carried with him on every speaking tour.

“In Peter Pan, we learn that fairies die when people don’t believe in them,” Pieters said. “In the stage adaptation, Peter Pan turns to the audience and says, ‘Tinkerbell is dying because people don’t believe in fairies. If you believe in fairies, clap your hands.’ And for decades, people have applauded like crazy to bring Tinkerbell back to life. At a time when so many of us who were called 'fairies' were dying, it was important for us to believe in ourselves enough to be present for one another when our lives were at stake. That was symbolized by the fairy wand.”

Ultimately, Pieters’ message, and his very life itself, are full of hope for those living with HIV and AIDS. “I hope and pray that nobody else is infected with AIDS,” Pieters said. “If you are, know that a full, long life is still possible with proper treatment.”

And perhaps, a touch of fairy dust.